Hi, Laura here. Take a look at how I developed the stories in Making the Shrine.

Each story is different, but at heart the process was the same each time: research, consultation, scripting and drawing different draft versions before drawing the finished pages which appear in the book.

This process involved learning, reflection, adjustments, and quite literally, going back to the drawing board. It took time, but I wasn’t in a rush.

Reflecting on the experiences of people who participate in war is remembrance. For me, the process of developing these stories provided a deep and real experience of remembrance: a specific kind of engagement with the past, a combination of historical attention with recognition and empathy.

The spotlight story here is set in 1942 and is called “Service”.

Before you read on: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this page contains images and names of deceased persons.

My starting points for making a story about the Shrine in the 1940s were about the fact that the Second World War was a radically different experience of war for Australians, and it also changed - broadened - the meaning of the memorial.

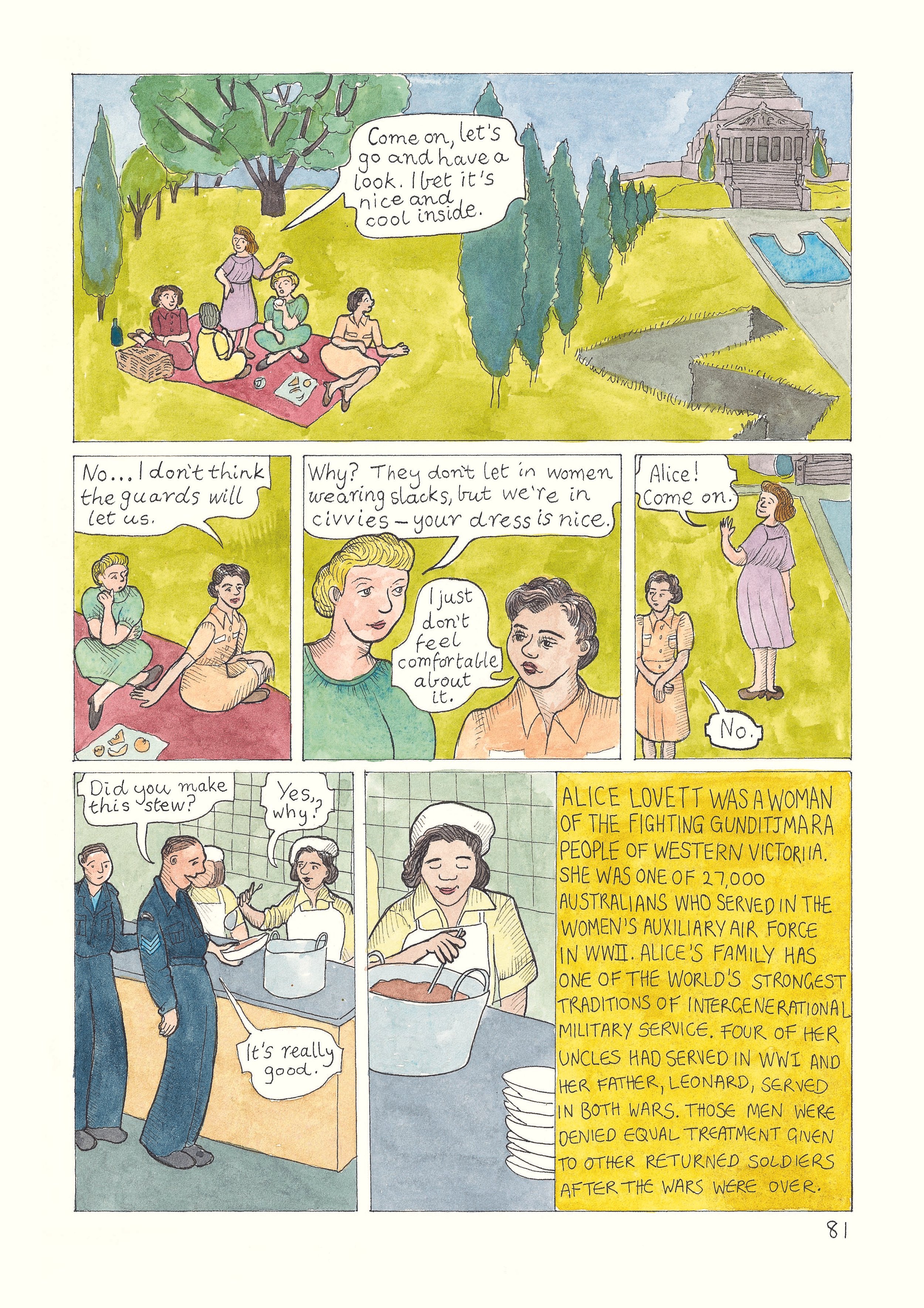

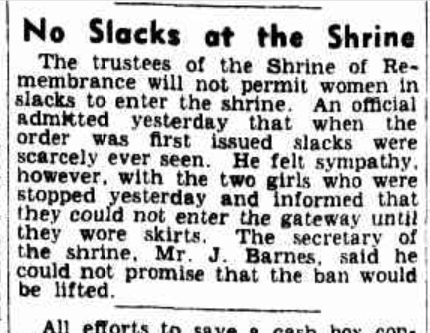

I wanted also to acknowledge that with these huge and rapid changes, the Shrine was sometimes a complicated place for people who had served and sacrificed in war, but didn’t see themselves acknowledged there.

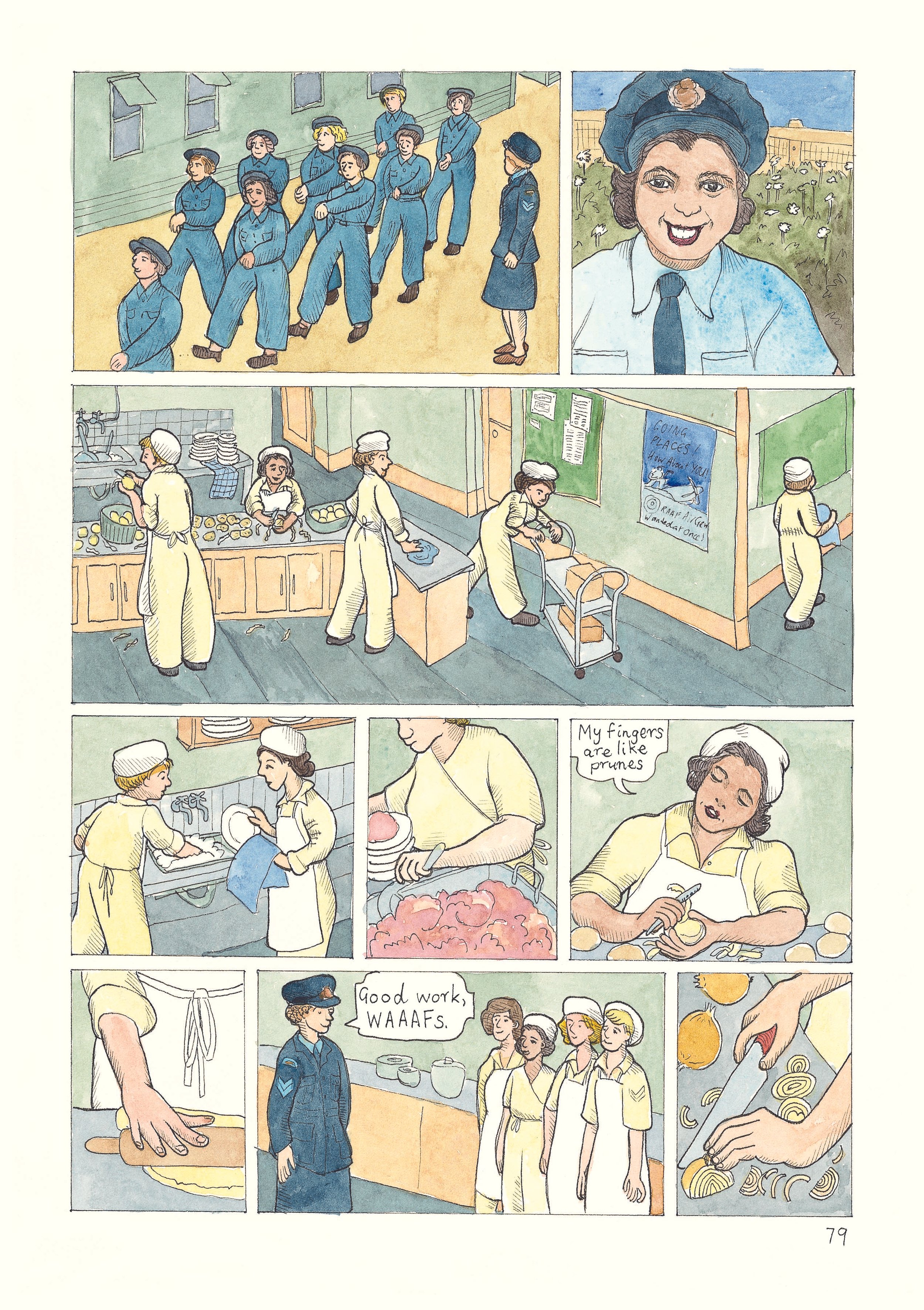

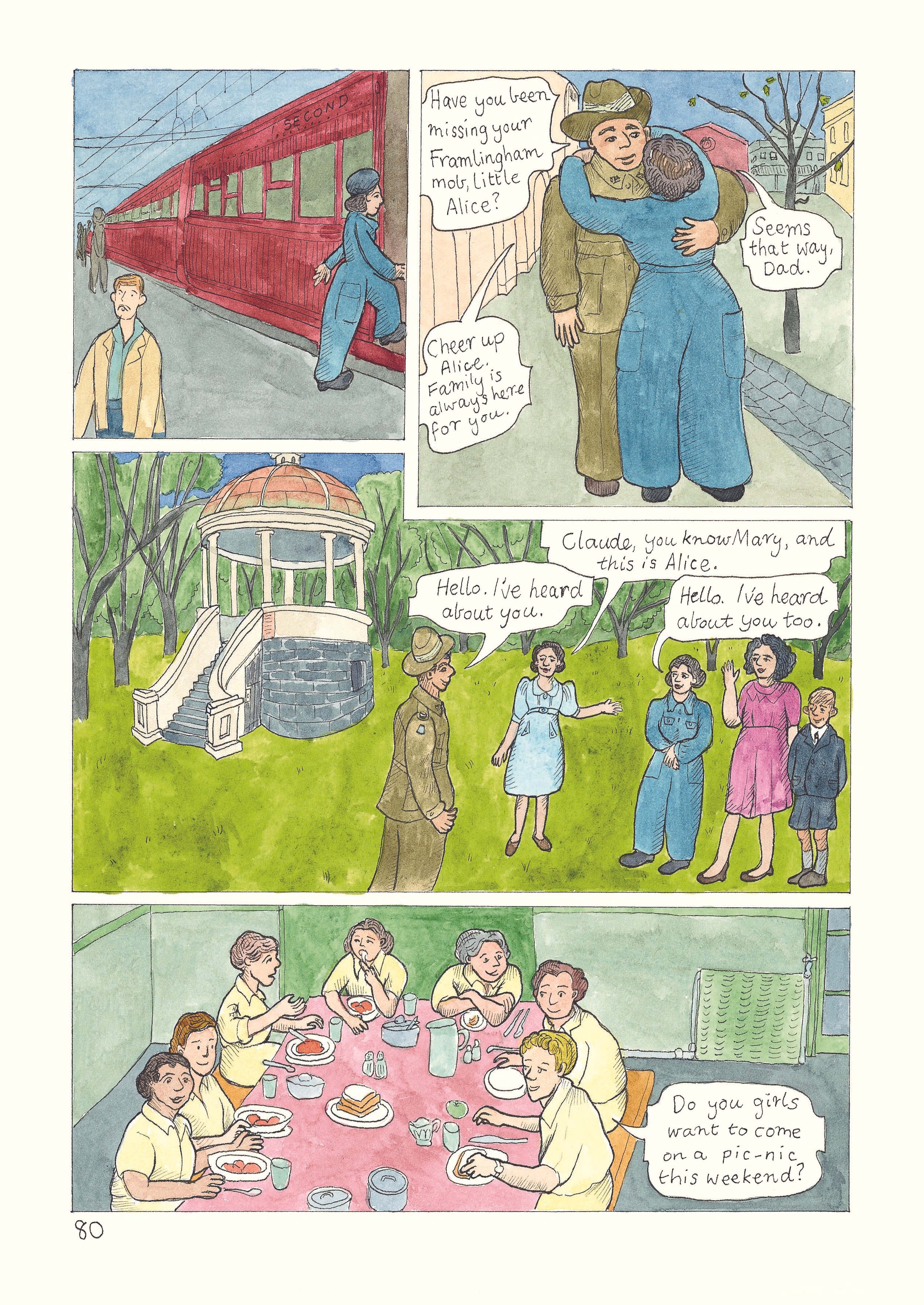

I knew about Alice Lovett, a young Aboriginal woman, who had served in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), and I wanted to interpret her story. I didn’t know (and still don’t know) whether Alice ever attended the Shrine: in my story, she’s invited by friends to go inside, but she isn’t comfortable about it, even though she is a service person herself, and multiple members of her family had served in the First and Second World Wars. So the story in the book is a blend of historical interpretation and imagined extrapolation.

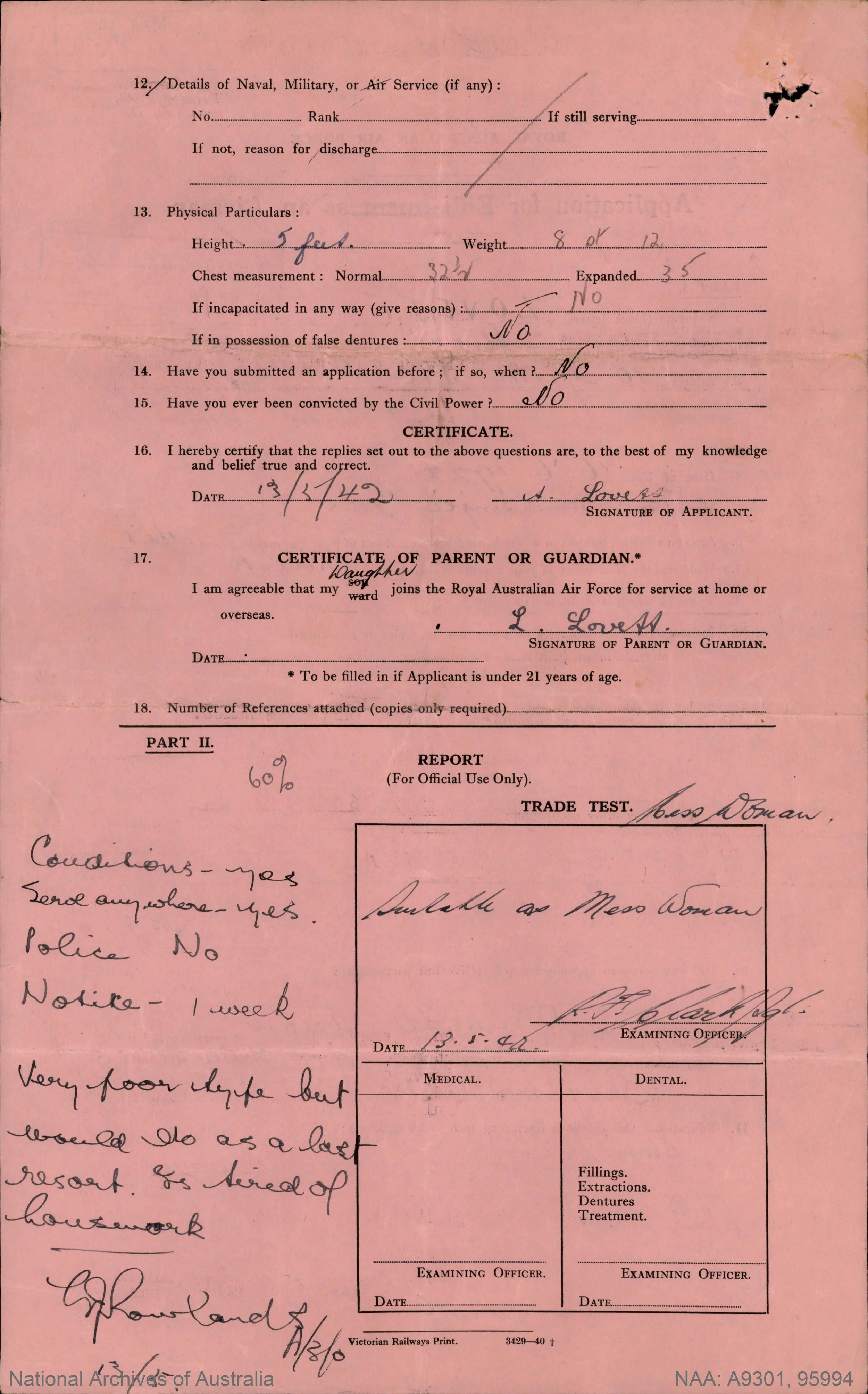

I began by gathering resources from public archives - the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia - to learn about Alice’s wartime service - what she did, where she worked, what the places and people looked like.

And then I wrote a script and did a pencil draft of a story.

It was important to me to consult and collaborate with Alice’s family members. I had the patient and generous help of one of Alice’s daughters in shaping this story. With her advice, the story changed quite a bit from the first pencil version. She shared beautiful family photos and memories and gave good suggestions. The story became significantly better as a result: less abstractly about women servicepeople in the 1940s, more particularly about how it was for Alice (seen of course through her daughter’s memories and reflections.)

In the finished story, it’s clear that Alice’s time in the WAAAF was a happy one for her, full of good work, time with friends and family, and it’s when she met Claude McDonald, her husband-to-be. But at the same time, her experiences of discrimination within the service are not glossed over.

Alice’s daughter drew my attention to something on Alice’s enlistment papers: at a time when the military was crying out for women to enter the services, someone saw fit to write a dismissive comment on Alice’s enlistment form to the effect that she ‘would do as a last resort’. There are overtones of race and class prejudice in this comment. As an Australian of Celtic heritage I can only imagine the kind of pain inherent for Aboriginal people and family members in reading things like this written by officials about someone like Alice. But I could also see, thinking about how her daughter talked about the incident, and advised that it should be part of the story, that it’s important that uncomfortable historical truth is faced and acknowledged. So this became the basis of the final cover drawing for the story, instead of the comparatively neutral sketch of a queue outside the enlistment centre which I’d begun with.

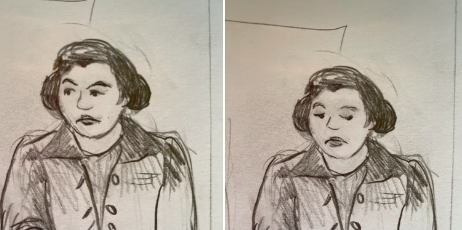

Working in drawings meant it was possible to show Alice’s daughter five different sketches of her face with different reactions to being disrespected, and to ask “how do you think your mother would have responded in that situation?” We settled on a face which conveyed disapproval, but standing her ground.

Here’s the finished story.